Is the "Safety" of Cash Silently Costing You Your Retirement?

Holding a healthy amount of cash in your accounts can feel incredibly safe, can’t it? In a world of market ups and downs, seeing that stable balance provides a sense of security and control. Especially over the past couple of years, when interest rates on savings accounts and money market funds have been attractive, it’s seemed like a smart, simple choice. Many people have thought, "Why risk my money in the market when I can earn a decent return right here in cash?"

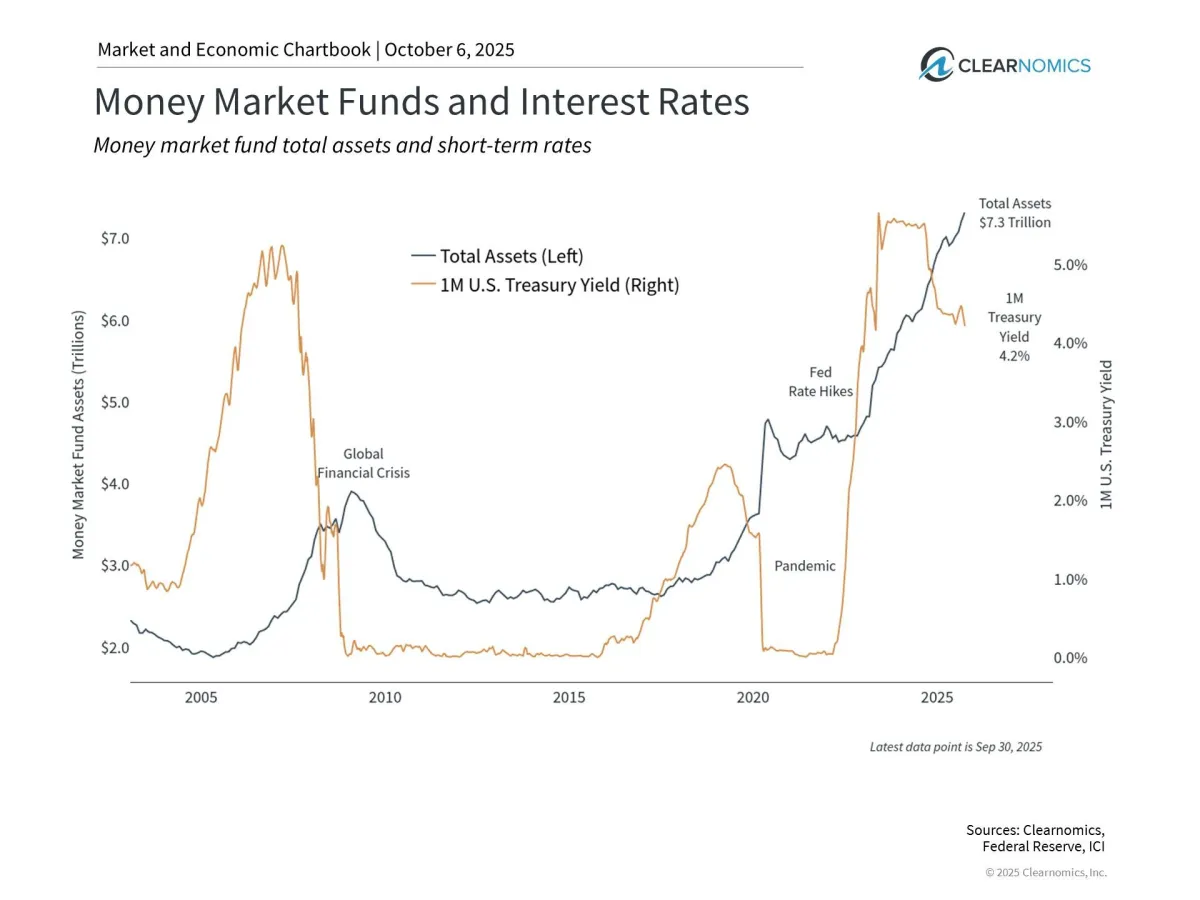

That’s a perfectly logical question. In fact, investors currently have a record $7.3 trillion sitting in money market funds alone, a number that has nearly doubled since before the pandemic. It shows that many people are seeking that feeling of safety.

But here’s the thing I always want to explore with my clients: What if that feeling of safety is just an illusion? What if holding too much cash is actually one of the quietest ways to undermine your long-term retirement plan? Let's pull back the curtain on the two hidden costs of holding too much cash.

The First Hidden Cost: The Slow Leak of Inflation

The most significant risk to your cash isn't a market crash; it's the slow, silent erosion of its buying power. We all know this as inflation. The dollar amount in your account might look the same, but what it can actually buy at the grocery store, the gas pump, or the doctor’s office shrinks a little bit every single year.

Think of it this way: Your retirement savings need to do more than just exist; they need to grow faster than your living expenses do. Cash rarely accomplishes this.

Let’s look at a real-world example. This first chart shows the interest income you might earn on $100,000 invested in 6-month CDs. Right now, that might be about $1,700 in interest—which sounds okay on the surface. But the chart also shows the real income after accounting for inflation. And what does it show? A loss of over $1,200 in purchasing power.

You’re earning interest, but you’re still going backward. It’s like being on a treadmill. The interest you earn is your "speed," but inflation is the speed of the belt. If the belt is moving faster than you are, you’re losing ground no matter how hard you run.

The Second Hidden Cost: The Reinvestment Rollercoaster

The other issue with relying on cash or very short-term investments is something we call reinvestment risk. That great interest rate you see today on your money market account or 6-month CD isn't permanent. It's a temporary offer.

When that CD matures in six months, you have to take that money and find a new home for it. But what if interest rates have dropped by then? You’re forced to accept a lower return. This creates a constant, stressful cycle of chasing yields and worrying about where rates will go next.

For a retiree who needs predictable, long-term income, this is a tough way to live. It makes it nearly impossible to build a reliable income plan. This is very different from, say, a 10-year Treasury bond, where you can lock in a specific yield for an entire decade, giving you a much clearer picture of your future income.

The True Engine of Lasting Wealth

So, if cash can't protect our purchasing power, what can? For generations, the answer has been consistent: owning a piece of great businesses (stocks) and lending money to stable governments or corporations (bonds).

History makes a powerful case. This next chart shows what would have happened to a single dollar invested back in 1926.

Because of inflation, that $1 from 1926 would need to be $18 today just to buy the same amount of goods.

If you had invested that $1 in safe 10-Year Treasury bonds, it would have grown to $115.

And if you had invested that $1 in the stock market, it would have grown to an incredible $19,000.

This isn’t about chasing risky returns or timing the market. It’s about a fundamental principle: to build a financial house that can last for a 20, 30, or even 40-year retirement, you need an engine for growth that significantly outpaces inflation over the long run.

Putting Your Cash to Work

Now, let me be very clear: I'm not saying cash is bad. Cash is a vital tool in your financial toolbox. But its job isn’t long-term growth. In a well-built retirement plan, cash should serve two specific purposes:

Your Emergency Fund: This is your safety net. It should hold about 3 to 6 months of essential living expenses in a place that’s instantly accessible for life’s unexpected curveballs.

Your Short-Term "War Chest": This is money you’ve set aside for specific, large expenses you know are coming in the next year or two—things like property taxes, a planned car purchase, or a big family trip.

The danger lies in the excess cash—the money beyond these two jobs that is sitting on the sidelines, silently losing its power. Your goal isn’t to be "in the market" or "out of the market." It’s to ensure every dollar you have is working toward your specific goals in the most effective way possible.

Is your cash serving its proper role, or is it secretly costing you the comfortable retirement you’ve worked so hard for?